Experiential Learning

Definition

Experiential learning is the strategic, active engagement of students in opportunities to learn by doing and reflecting on those activities, which empowers them to apply their theoretical knowledge and creativity to real-world challenges, including those in workplace and volunteer settings.

Well-planned, supervised and assessed experiential learning activities enrich student learning and promote intellectual development, interdisciplinary thinking, social engagement, cultural awareness, teamwork, and other communication and professional skills.

Experiential learning can include:

- Interactive simulations

- Industry or community-sponsored research projects

- On-campus work

- Teaching labs

- Performance-based learning

- Capstone projects

- Internships

- Apprenticeships

- Practicums

- Campus incubators

- Applied research projects

- Co-ops

- Field experience

- Clinical placements

Explanation

There are many different types of experiential learning that can be integrated into in-person, online, and flexible hybrid learning. In addition to the type of experiences, you may also wish to explore the types of learning that can be accomplished via these experiences. They include active learning, problem-based learning, project-based learning, service learning, and place-based learning (Wurdinger and Carlson, 2009). These approaches can be applied to various experiential learning opportunities that are already in place at Ontario Tech. It is important to consider that some disciplines may be better suited to some types of experiential learning versus others.

Table 1: Types of experiential learning offered by Ontario Tech Faculties.

|

Faculty |

Co-op |

Internship |

Capstone |

Practicum |

Lab |

|

Business and IT |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

||

|

Education |

|||||

|

Engineering and Applied Science |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

|

Energy Systems and Nuclear Science |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

|

Health Science |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

||

|

Science |

✔ |

✔ |

|||

|

Social Science and Humanities |

✔ |

Table 2: Strategies for student engagement in experiential learning.

|

Active Learning |

Problem-Based Learning |

Project-Based Learning |

Service Learning |

Place-Based Learning |

|

|

Co-op |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

||

|

Internship |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

||

|

Capstone |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

|

Practicum |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

||

|

Lab |

✔ |

✔ |

Application

1. Consider Faculty-, discipline-, and student-specific learning opportunities when planning for engagement through experiential learning.

It is important to consider that some disciplines may be better suited to some types of experiential learning versus others. Some disciplines may more obviously lend themselves to a project-based opportunity such as a Capstone project because of the nature of the skills of the student, but also of the expectations of industry (e.g., entrepreneurial problem-based learning is in high demand in particular industries).It is also important to consider the cohesiveness of planned experiential learning approaches with the target student population (Cantor, 1995, p. 82). Students who are early in their academic careers may need extensive scaffolding in place to successfully complete an experiential learning activity, while senior or graduate students may be more able to actively experiment within the parameters of the activity.

2. Encourage deeper learning by allowing time for reflection on and application of learning.

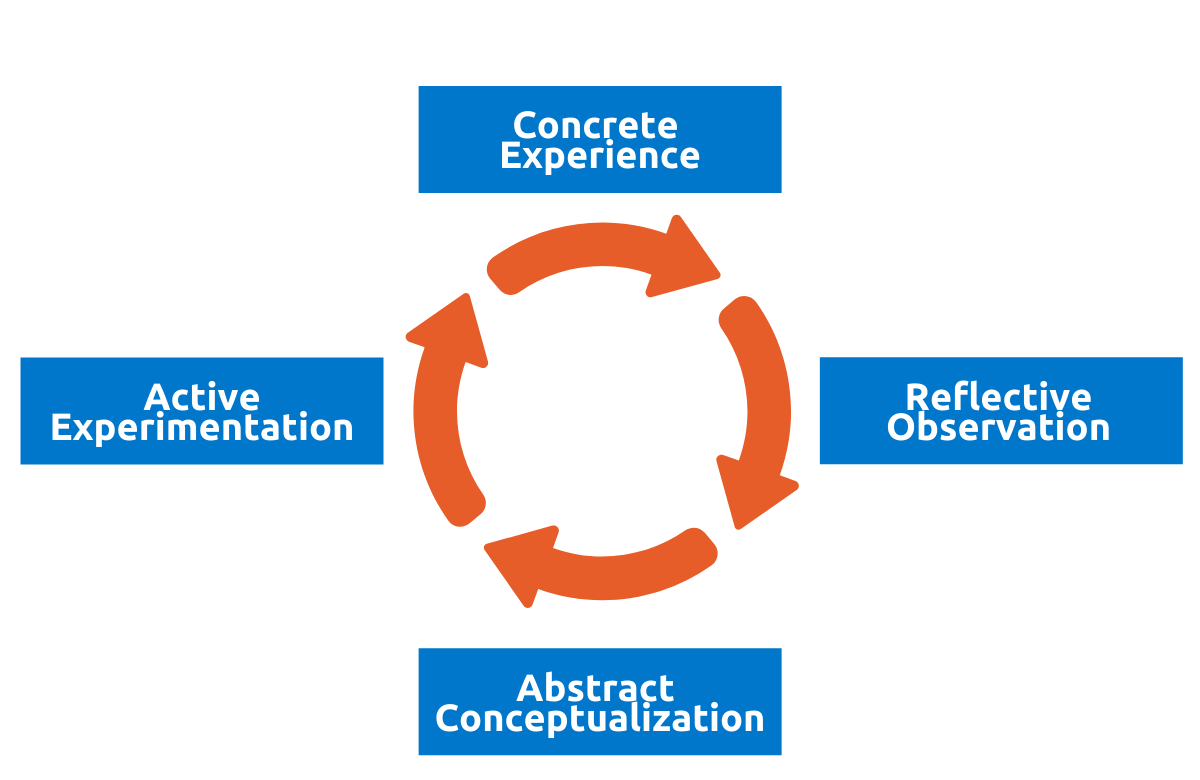

The Experiential Learning Model proposed by Kolb (1984) encourages a cyclical process of experience, reflection, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation. In order to fully capitalize on the experiential learning process, and for students to gain the most influential learning, time for each of these stages should be accounted for in the planning process (Teaching and Learning Office, Ryerson University, 2012).

Figure 1. Kolb's Experiential Learning Model

The reflective component of the experiential learning cycle may be new for many Ontario Tech students, especially those in STEM disciplines. Support is available online that instructors can use to introduce students gradually to the process of impactful reflection.

3. Allow students time in class to actively experiment.

Kolb’s model of experiential learning (1984) encourages instructors to view experiential learning as a cycle, where students are presented with an experience, and learn through observation, conceptualization, and further experimentation. Often, students (and instructors) can feel uncomfortable with this type of learning experience; they are not given all the “answers” the way they would in a traditional, lecture-style experience. They may have difficulty executing an experiential learning task in the way that was envisioned during the planning process, thus it may take dramatically longer to complete. Instructors should allow for this during class time and build in the extra time needed to make multiple attempts at an activity and to record and consider reflections on the experience (Wurdinger & Alison, 2017). Instructors should consider the implementation of experiential learning in their courses in an iterative manner, to evaluate successes and room for improvement as each activity is delivered.

4. Align activities with learning outcomes.

Much like designing experiential learning opportunities to align with student needs, activities should also align with course learning outcomes or have accompanying learning outcomes so all stakeholders are aware of criteria for success. This helps experiential learning maintain its academic integrity with both faculty and students so it does not appear “gimmicky” or out of place. Having clear alignment with learning outcomes assists the instructor or evaluator in designing assessments and performing evaluations, while students are better able to see how an opportunity “fits” with their academic and career vision (Wurdinger, 2005).

5. Emphasize the importance of self-reflection in the learning process.

The role of self-reflection on experiential learning is not an insignificant one. Chapman, McPhee, and Proudman (1995) indicate that the reflective portion is what ties the information or lesson together to allow for additional learning to occur as the result of the experience. In addition to providing students time to reflect on learning during class, there is also the potential to include this part of the EL process in course assessment. However, instructors must realize that it does take time for students to learn the practice of influential reflection of learning. Opportunities to practice good reflection is necessary, especially for new students (Chapman et al., 1995).

6. Consider experiential learning to reinforce higher-level thinking and application of theory.

While experiential learning is important for students to gain the skills necessary to be successful in the future of work, experiential learning can also be an important contributor to the intellectual development of students. Deep learning and intellectual development can be furthered through thoughtful integration of experiential learning in course material (Armstrong & Fukami, 2009). While lectures and typical assignments reinforce the necessary skills of knowledge and comprehension, higher order intellectual skills in analysis, evaluation, and creation are necessary for students in well-designed EL experiences (Cannon & Feinstein, 2014).

7. Encourage interdisciplinary thinking by providing students with opportunities that closely mimic the structure of organizations in real life.

Changes in how workplaces are structured, how information is obtained, and how tasks are performed require graduates to have not only a deep understanding of their field, but also a broad understanding of other disciplines with which they might work. New graduates will need to show an understanding of collaboration and teamwork as well as social and cultural understanding. It is unlikely that future graduates will encounter an employment opportunity where they practice their own discipline with no interaction with others. Furthering an understanding of the functions of other disciplines and how best to work with them builds essential communication and other professional skills and increases the authenticity of an opportunity, in addition to developing higher level thinking (Knobloch, 2003).

8. Provide flexible opportunities for employer or partner engagement in experiential learning.

The kinds of experiential learning offered to students vary greatly depending on student preferences, types of courses, institutional support, and faculty engagement. With all these variations, engaging employers or other EL partners on a consistent basis can be challenging. That said, some flexibility should be considered, giving employers/partners opportunities to “try” different types of experiential learning partnerships to see what fits best with their structure and availability. Flexible options for participation can introduce partners to the academic nature of EL gradually, giving both sides the opportunity to find a common ground for understanding of the expectations of students, partners, and institutions (The Higher Education Academy, 2013).

Examples

-

Faculty of Social Science and Humanities – Online Practicum Course

A sophisticated online version of the Faculty’s typical practicum course was created so that students can complete a practicum experience off-campus, whether they are in another country or are too far from Ontario Tech campus for the live class commute. Without the online version, students juggling demanding class, work, and personal schedules were unable to fully experience a practicum, or, more likely, to avoid the experience altogether.

-

Faculty of Education – Engaged Educator Project

The Engaged Educator Project (EEP) is an action-oriented educational project where students engage with the various stakeholders of an organization, network, or community of practice on an issue or opportunity that is meaningful to the group, leading toward meaningful social or structural change for the group. This project is designed to help students make connections between what is learned in class and the potential for impact the learnings have on society. It also allows for flexibility, so students are able to engage with stakeholders on a project that is meaningful for themselves and their educational path.

-

Faculty of Energy Systems and Nuclear Science – Field Trips

The Canadian Engineering Accreditation Board (CEAB) sets standards for the academic requirements of accredited engineering programs in Canada. The technical environment expects the student to increasingly integrate and practice, using hard- and software tools, required and/or identified task(s) as a stand-alone technical work output or (more often than not) as a contribution to a larger technical project/initiative. The Faculty of Energy Systems and Nuclear Science developed a number of new experiential learning opportunities with the Career Ready Fund to link the graduate attributes and learning outcomes indicated by the CEAB with hands-on experiences during field trips to actual engineering operations, encouraging the acquisition of CEAB-required skills while increasing their knowledge of employment scenarios.

-

Ontario Tech - Lord Ridgeback Project, Partnered with Durham College

Students from Ontario Tech (Forensic Science, Medical Laboratory Science, Collaborative Nursing Registered Practical Nursing-to-Bachelor of Science in Nursing) and Durham College (schools of Justice & Emergency Services, Health & Community Services and Media, Art & Design) participated in a disaster simulation exercise on the university’s and college’s shared campus in north Oshawa. As part of the simulation, there was a noticeable presence of emergency vehicles on campus, volunteers acting in distress and being moved around campus on stretchers, and the use of smoke machines. Participants put their in-class training into action and gained vital understanding of how health-care, emergency and legal service providers and the media must work together during an emergency. In addition to collaborating with students in their own institutions, participants in the Lord Ridgeback Project also worked with students in disciplines at the partner institution. This added authenticity to the Project, encouraging students to call upon communication skills as well as technical knowledge.

Resources

Learn about experiential learning at Ontario Tech:

References

Armstrong, S. J., & Fukami, C. V. (Eds.). (2009). The Sage handbook of management learning, education and development. Sage.

Cantor, J.A. (1995). Experiential Learning in Higher Education. Washington, D.C.: ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report No. 7.

Chapman, S., McPhee, P., & Proudman, B. (1995). What is Experiential Education?. In Warren, K. (Ed.), The Theory of Experiential Education (pp. 235-248). Dubuque: Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company.

Knobloch, N. A. (2003). Is experiential learning authentic?. Journal of Agricultural Education, 44(4), 22-34.

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Centre for Excellence in Learning & Teaching, Toronto Metropolitan University (2021). Best practices in experiential learning. https://docs.google.com/document/d/1nixBZ0jTcH2iLjG1bKS5BpT_7V94W3ZA1d5ezv-lBok/edit

The Higher Education Academy (2013). Flexible pedagogies: Employer engagement and work-based learning. https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/flexible-pedagogies-employer-engagement-and-work-based-learning

Wurdinger, S.D, & Allison, P. (2017). Faculty perceptions and use of experiential learning in higher education. Journal of e-learning and Knowledge Society, 13(1).

Wurdinger S.D, & Carlson J. A. (2009). Teaching for experiential learning: five approaches that work. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers.